Annual Message from the Director

2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007

The year has started off with another mega disaster, this one even more complex and extended than those that have occurred since 2004, and not yet fully under control as I write this. The northern Japan earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster underscore just how interconnected environmental and human systems are, and the severity of the consequences when disruptions exceed our immediate capacity to cope. The added dimensions of radioactive contamination and potential reactor core meltdowns have dramatically increased the challenges and risks for those struggling to contain the damage and to deal with the severe consequences of the initial events. Our thoughts and sympathies go to the many victims of the northern Japan earthquake and tsunami and those working to end the nuclear crisis there.

|

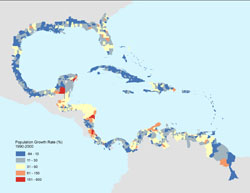

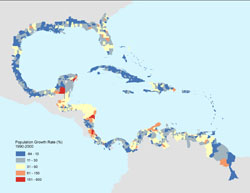

| Population growth rate estimates

for the Gulf Coast and Caribbean Basin over the 10-year period from 1990–2000 are from a collaborative research project between Columbia University, University of Puerto Rico, Sonoma State University, University of California, Santa Barbara, and Universidad Nacional de Tucumán (Argentina), “The Impact of Economic Globalization on Human Demography, Land Use, and Natural Systems in Latin America and the Caribbean.” |

This disaster illustrates again the vital importance of long-term data and information in disaster planning and risk management. The affected coastal regions in Japan had made substantial investments in coastal protection, and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear facility was designed to withstand an earthquake of magnitude 7.0 and an associated tsunami of up to about 6 meters (compared with an estimated magnitude of 9.0 and wave height of 14 meters at the plant, on March 11). This was apparently based on seismic data from the past four to five decades. However, at least four quakes of magnitude 8 or more occurred over the past 400 years—but were not taken into account when selecting the “worst case scenario” used in designing the nuclear power plant and coastal barriers. For irregular events like massive earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, very long time series of relevant data are vital to improving assessments of the likelihood of future events, and in turn improving the planning and design of facilities and systems to reduce risks.

Mega disasters are not the only reason for extending our knowledge back in time for centuries or millennia. Long time frames are also essential in addressing issues such as climate change and sustainable development. Although we tend to think of coastlines and ecological zones as relatively fixed over time, on time scales of many decades or longer there are often substantial changes in sea level, shifts in rainfall patterns, river flows, and forest cover, and changes in the frequency and location of drought, flood, and fire. Better data and information on past changes can help determine how best to optimize and protect agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, urban development, transportation networks, and other human activities and infrastructure in a changing environment.

|

| The Terra Viva! SEDAC Viewer enables the integration and visualization of socioeconomic and environmental data, including climate change data. |

There are multiple challenges in developing scientifically sound, consistent, and useful data on time scales of centuries or even just decades. Special techniques are needed to infer environmental conditions in the distant past, and these data may not be entirely consistent with measurements obtained from current instruments and sensors. The digital revolution is only a few decades old and continues to change how we deal with data—how we collect and store data, process and analyze them to produce value-added information and knowledge, and share and disseminate the results for both scientific and applied users. Satellites, handheld sensors, computer models, and social networks are generating vast amounts and new types of data, not only on environmental phenomena but also on human behavior and perceptions. Scientists, data centers, libraries, and others are struggling to cope with both the opportunities and challenges posed by this increasing flood of data and information.

CIESIN is working to improve not only our present understanding of human-environment interactions but how these interactions have evolved over time. For example, as part of a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant, Marc Levy, Susana Adamo, and colleagues have been examining population growth and land use change throughout Latin America over two decades. Marc is also part of an NSF grant led by Lamont associate research professor Brendan Buckley, who is examining the impacts of drought on Cambodia’s ancient Khmer civilization at Angkor over many centuries.

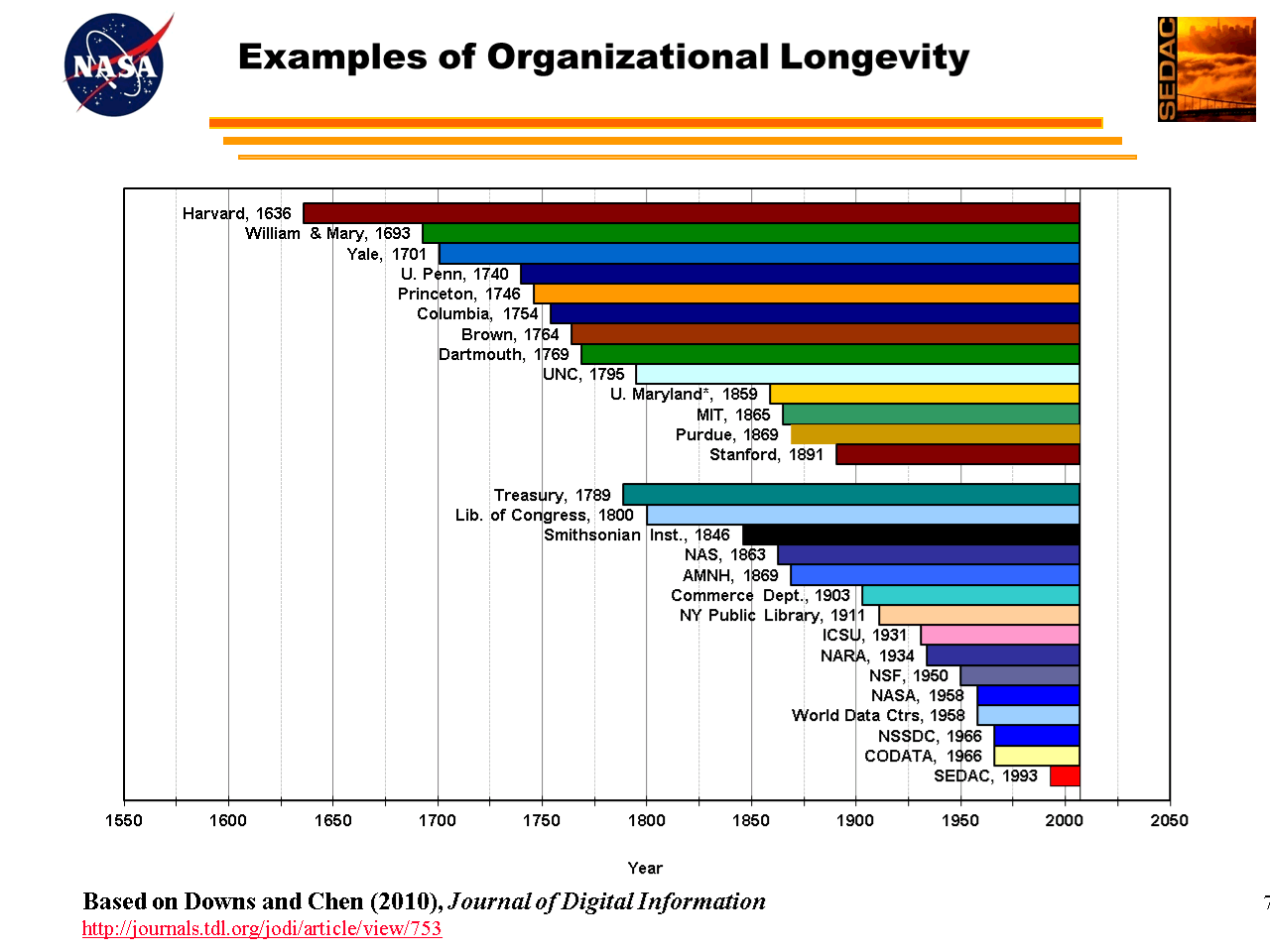

At the same time, CIESIN is also exploring ways to ensure that our existing data and information archives are properly preserved for use in the future. Next month we will be releasing a new online resource center for preservation of geospatial data, developed in collaboration with the Library of Congress. We continue to work with the Columbia Libraries on digital preservation issues, recognizing that universities and their libraries are outstanding examples of data and knowledge preservation and use over more than 250 years in the United States—and longer in other parts of the world. We are also helping to develop new standards for certifying trusted digital repositories, and continue to collaborate with the International Council for Science (ICSU), the ICSU Committee on Data for Science and Technology (CODATA), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and other groups on long-term stewardship of scientific data.

In the end, the only way to keep extreme events like earthquakes, tsunamis, floods, droughts, and tropical storms—and technological, health, and societal threats like nuclear incidents, pandemics, and terrorist attacks—from turning into major humanitarian disasters is through careful long-term planning, substantial investments in protective infrastructure, and development of appropriate response capacities to deal with such situations. All three of these activities require high quality, long-term data and information as well as the tools and systems necessary to use this data and information when needed both in disaster planning and response. Even in times of tight budgets, investing in better data and knowledge has substantial short- and long-term benefits; and not investing in them means we will undoubtedly continue to be surprised by—and suffer needlessly from—even more serious mega disasters in the future.

Bob Chen

April 11, 2011 |